Monday,

August 14, 2023

11:38am

Our September and October exhibit explores the history and impact of decades of discriminatory housing practices in Worthington and central Ohio.

Following a real estate bubble in the 1920s and the 1929 stock market crash, the United States was plunged into the Great Depression. Millions were unable to pay their mortgages and faced the loss of their homes. The federal Home Owners' Loan Act, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, aimed to "provide emergency relief with respect to home mortgage indebtedness." To carry out the provisions of the act, it created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), which made low-interest loans to homeowners struggling to pay their mortgages.

Throughout the 1930s, the HOLC created "residential security maps" of more than 200 cities, meant to indicate the level of security for real estate investments, with different colors designating the percentage of properties in the area eligible for federal mortgage insurance. The areas considered most desirable for lending purposes were designated Type A and outlined in green. "Still desirable" areas were Type B and outlined in blue. Type C areas were "definitely declining," and were outlined in yellow. And Type D neighborhoods, considered "hazardous" for mortgage support, were outlined in red.

The federal government deemed these "redlined" areas completely ineligible for federal mortgage insurance. It's no coincidence that redlined areas were often neighborhoods where Black residents lived.

While the maps were not made public at the time, Black residents felt their impact as they were unable to obtain home mortgages backed by government insurance programs. This common way for Americans to build wealth was simply unavailable to them. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned discrimination in real estate and mortgage lending, including racially motivated discrimination, but the impact of unequal access to real estate wealth through those decades has persisted.

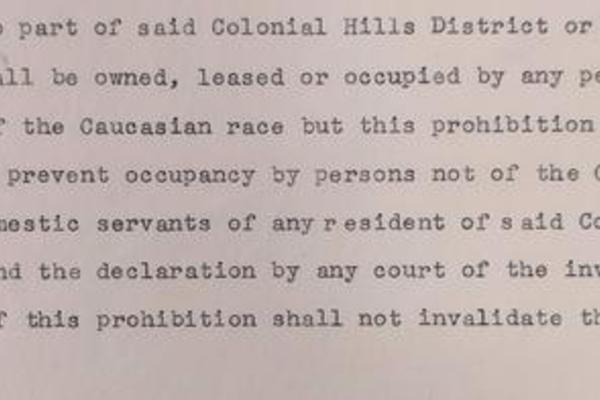

The redlining maps were not the only factor driving racial discrimination in housing. The 1936 map of the Columbus area shows no redlined areas of Worthington, only blue and yellow neighborhoods. However, beginning in the 1920s, new housing developments in Worthington were platted with restrictive covenants, limiting ownership and occupancy of the homes to white residents. An example of a restrictive covenant from the Colonial Hills neighborhood reads:

No part of said Colonial Hills District or any building thereon shall be owned, leased or occupied by any person other than one of the Caucasian race but this prohibition shall not exclude or prevent occupancy by persons not of the Caucasian race as domestic servants of any resident of said Colonial Hills District and the declaration by any court of the invalidity of any part of this prohibition shall not invalidate the remainder thereof.

This tactic to restrict homeownership was being used all over the country and central Ohio, and Worthington was no exception. In fact, the Federal Housing Administration required racial restrictions for new subdivisions to qualify for federal mortgage insurance. Other neighborhoods developed with restrictive covenants included Riverlea, Detrick Estates and Medick Estates.

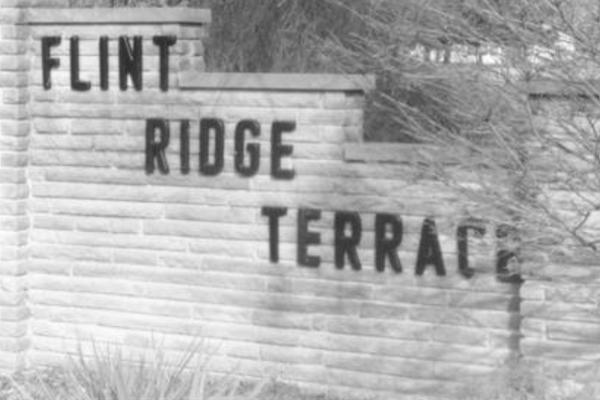

Flintridge Terrace, a neighborhood just north of Worthington off of Flint Road, was developed by Black residents who wished to own their own homes but faced discrimination in other neighborhoods throughout central Ohio. In 1958, Robert and Vera Johnson, a Black couple, purchased land to develop the 12-acre neighborhood. Robert was a World War II veteran and an electrician. As described in "Forward with Brotherhood," a 1969 booklet by the St. John African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church:

Mr. Johnson has a master mind for seeing things grow and develop to its full extent. He, being one of our outstanding leaders in Civic affairs, also knew the plight of his Negro Brothers. Suburban property for a Negro to build a new home was almost nil. Unselfishly, Mr. Johnson spent many hours and dollars and had two roads built in Sharon township. Melyers Court and Bertson Place. The Wheatleys [Alexander and Leona] continued the road, Bertson Place. We now have a beautiful area…known as Flint Ridge Terrace.

The 1998 book "Linking Past to Present: An Historical Account of Flintridge Terrace and Its Surrounding Areas" describes the development of the neighborhood. The property purchased by the Johnsons was platted into one-half acre residential sites, with each home built to the owner's specification. In 1961, the roads in the area were dedicated to Sharon Township to ensure they would be serviced and maintained without additional cost to homebuyers.

As shared in "Linking Past to Present":

Because many of us, as African Americans, had experienced indifferences and sometimes rejections in our early efforts to purchase homes, the aspiration for a beautiful, well-kept neighborhood has been strong. When building issues occurred that threatened to destroy or ‘chip away’ at the security and serenity of the neighborhood, the families stood together and fought back…The Sharon Flint Residents' Association was organized in 1965 to solidify the efforts of the neighborhood, retain legal assistance if needed and to develop and exert political clout when necessary. The first challenge was an effort to change the zoning in the area to allow the construction of a steel fabricating plant…A lawyer was retained and with the support of Flint, Park, and Lazelle Road residents, the request was denied.

The book lists numerous other efforts to introduce industrial operations to the area, which would negatively impact property values and quality of life. This practice, known as expulsive zoning, was a common occurrence in African American neighborhoods throughout the country. In the examples given in the case of Flintridge Terrace, these efforts were denied.

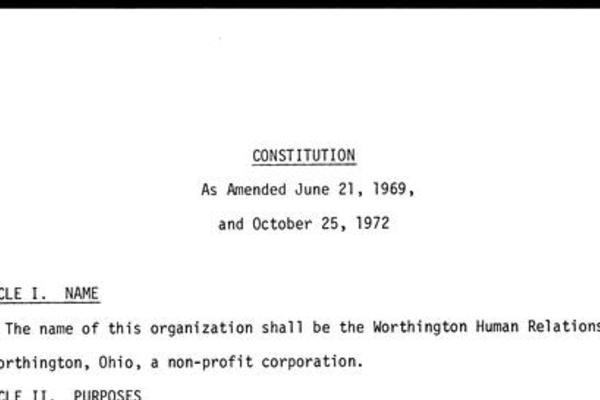

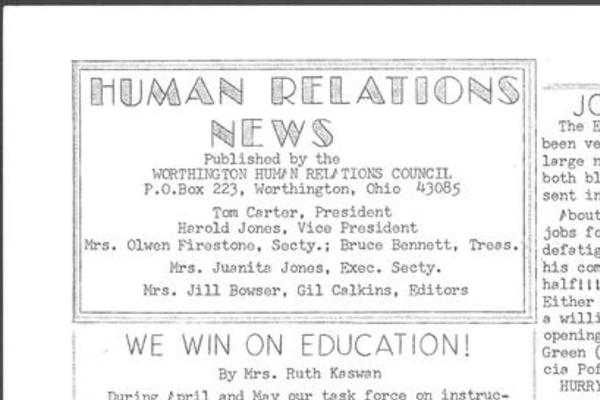

In 1963, five years before the passage of the Fair Housing Act, a group of residents in Worthington took matters into their own hands in addressing racial inequality in housing, employment and schooling. Two Worthington residents, Harold Benson Jones, a lay member and musician for the St. John AME Church, and Kent Morehead, an associate minister for the Worthington United Methodist Church, found themselves frequently discussing social injustice in Worthington. They called together a group of residents, who formed the Worthington Human Relations Council (WHRC) in 1963.

For the next nearly 30 years, the WHRC worked for equality in housing, schooling, employment and public accommodations. The group assisted Black homebuyers in finding homes in Worthington neighborhoods and were successful in removing the third-party clause from housing contracts-- meaning neighbor approval of potential buyers was not required. The group was also instrumental in increasing the number of Black teachers hired in Worthington Schools, as well as having Black Studies added to the curriculum in 1970. And fighting hiring discrimination by Worthington businesses was a constant effort of the group.

While discriminatory housing practices are no longer legal in the U.S., the impact of these practices on generations of residents are still plain to see. Throughout central Ohio, businesses disappeared from redlined areas, and major freeways cut through neighborhoods. Studies have shown that once-redlined areas are higher in air pollution today, are hotter in the summer and residents experience greater disparities in health outcomes.

Residents of these areas missed out on decades of building wealth via homeownership. An October 9, 2022 "Columbus Dispatch" article cited Jason Reece, an assistant professor of city and regional planning at The Ohio State University's Knowlton School of Architecture: "Reece said that in 2016, the median net worth of white households ($171,000) was more than 900% higher than the median net worth of Black ($17,600) and Latino ($20,700) households." The 2022 U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts for the city of Worthington estimates its population to be over 90 percent white.

A statement given by the WHRC to the Worthington Board of Education in May 1978 rings true today: "If we do not know our neighbors, we all suffer. If we confine our contacts to only those who are identical to us in background, we deny ourselves the opportunity to grow and, in the case of young people, we deny them an important aspect of preparation for life in the larger community of the world."