Wednesday,

February 1, 2017

9:30am

February is Black History Month, and Worthington Memory is joining the celebration by highlighting several of the city's Black residents through the decades.

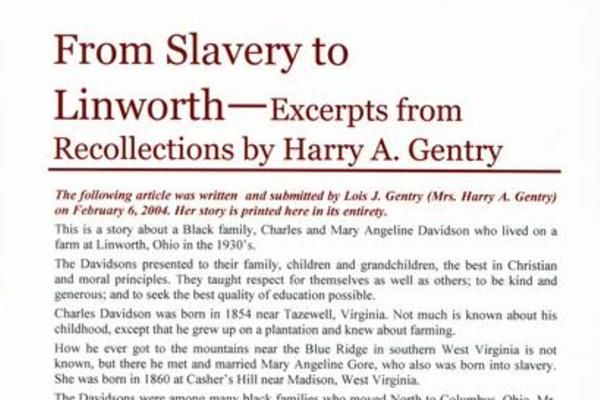

African Americans have been part of the city's history since the early 1800s. In 1807, four years after Worthington's founding, there are records of payments made to "Black Daniel" for working in Amos Maxfield's brickyard. In 1856, when the country was in turmoil over the issue of slavery, former enslaved people from Virginia became the first African Americans to buy their own home here. Henry and Dolly Turk purchased the house that still stands at 108 W. New England Ave., and their family owned it until 1895. Henry had bought his wife's freedom from slavery in 1838 and, according to an account by Lovisa Wright in 1904, "Henry and Dolly Turk were liked by all."

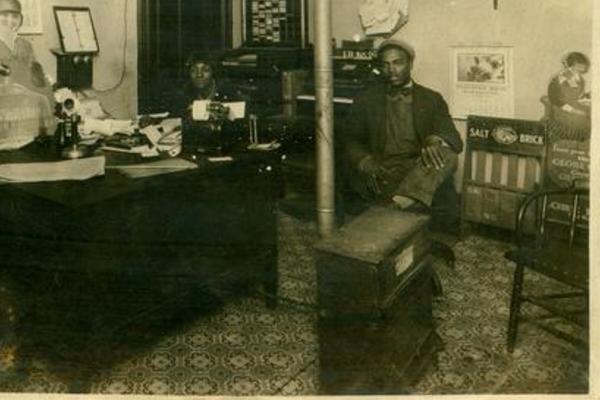

Several decades later, Squire Todd owned a successful moving company in Worthington, the Worthington Feed and Transfer Company. It operated from 1914 through 1934, when the Great Depression forced it out of business. A secretary for the company, Stacy Marie Calloway, was the daughter of John Kendall and Sarah Lee. The Lee family lived in the Worthington and Linworth area throughout the 1910s and '20s, and several of the Lee children attended Worthington schools.

Worthington's schools have always been open to Black children, but the curriculum did not always reflect the diversity of its students. Juanita Jones wrote about her experiences attending school in the 1930s and '40s in "Black Pioneers in Education," a booklet published by the St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church in Worthington. She wrote:

In thinking back to the period of time this Article refers to there was the same push for all students to learn the three R's, but for the black student the history or social studies class seemed to be barely related to him. The text and class room discussion mentioned his people only in connection with the slave trade, slavery in the South, the Reconstruction Period, or in "Uncle Tom's Cabin." There was very slight mention of Tuskegee Institute and George Washington Carver. In the literature books there were no compositions by black writers. If the teacher happened to read Huckleberry Finn to the class, you would hear some of the antics of his black friend. A few Negro spirituals were sung in music classes. It was almost impossible to get reference material or compositions by any outstanding black musician or writers.

Even in the nineteen-fifties, you could find only two books that were written by or about the black man in the Worthington Public Library; they were the collection of poems by Paul Lawrence Dunbar and a small book of brief character sketches of Carver, Booker T. Washington, Harriet Tubman, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Frederick Douglass.

Fortunately, things began to change in the 1960s and '70s, particularly when the schools began to hire Black teachers. The Worthington Race Relations Group became a school club at Worthington High School in 1970 and was immensely popular with students.

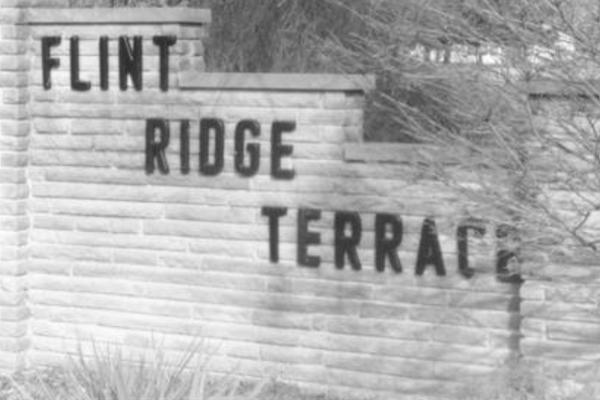

Black people also faced obstacles when buying homes in Worthington after World War II. One couple, Robert and Vera Johnson, planned and developed Flintridge Terrace, a community off Flint Road where numerous African Americans bought homes, but the developers of new neighborhoods such as Riverlea discriminated against Black homebuyers. The Worthington Human Relations Council was formed in 1963 to help address this issue and, along with federal fair housing laws, such discrimination was condemned by the community.

Worthington has not been immune to racial prejudice through the decades, but the efforts of dedicated individuals and groups such as the Worthington Race Relations Club and the Worthington Human Relations Council have shown that concerned citizens can bring about change for the better.